Stress, the Nervous System and Heart Rate Variability

A healthy heart should have a nice regular beat – right?

Well it isn’t that simple. Read on and find out why HRV or Heart Rate Variability, is one of the most important metrics you might want to measure, either for general health and wellbeing, or from an athletic performance point of view.

HRV is a measure of the variation in time between each heartbeat. And you thought it was regular? Well it turns out it’s not.

Your heart rate is one of the many things controlled by your autonomic nervous system. You can think of your autonomic nervous system as having two halves – the sympathetic nervous system (think the accelerator or go button) and the parasympathetic nervous system (the brake or stop button).

You might have heard these systems described as the fight or flight mechanism, or something similar. As your brain processes information, it sends signals around the body to prepare it for what it perceives may lie ahead. A car fails to stop at the stop light as your crossing the street – startled you instantaneously step back from the curve as the car races past – you can feel your heart pumping in your chest, your eyes focused on the threat. But wait a minute…who commanded that response? You did not consciously think about this entire sequence and response. If you did, you’d be squashed on the road right now, and evolution is too smart for that. This sympathetic response happened automatically in a more primitive part of the brain as part of the house keeping functions that happen as if by magic.

That night safe at home, well fed and tired from your active day your system starts to magically unwind as your parasympathetic system dominates-you relax, digest your food and then go to bed and sleep through the night. Safe in your own bed.

Or perhaps not. Perhaps you relive that terrible experience of the day haunted by your thoughts of your mortality. What if the car hit you? You could have been killed. Your heart pumps, you toss and turn in bed unable to settle. You cannot sleep. Your mouth is dry. Your stomach uneasy. You feel sweaty. Your respiration rate rises. – all these responses are a result of an overactive sympathetic nervous system driven by your own perceptions of the events earlier.

In the perfect world these two systems work in harmony to help us survive and flourish. But that is not always the case as the example above illustrates.

We all hear that stress is bad, but is that true? Not really. The human body requires a degree of stress to be healthy. There is good evidence to show that regularly stressing the body results in it growing stronger and healthier.

That stress can be anything from exercise stress such as lifting weights or jogging, temperature stress – such as a sauna or a cold plunge pool, mental stress such as solving a complex puzzle. These are all examples of healthy stresses to the body. Even examples of occasional fasting stress have been demonstrated to be beneficial for the human body.

But there are two important points here. The stress that you apply to the body has to be at an appropriate level and an appropriate duration.

If the stimulus is too low, it will not challenge the system enough to change. If the stimulus is too high, it will break the system. Equally, the stimulus must be of an appropriate duration to challenge the system, but again not too long to break it.

The body then needs a period of recovery to allow it to recover and grow stronger from the stimulus. Without the recovery the body often struggles to adapt and grow stronger and instead becomes warn down and finally breaks down.

So, you can think of optimisation of the human body being achieved through exposing the body to a wide variety of stressors, at an appropriate amount and an appropriate duration (enough to stress but not to break). This often stimulates the sympathetic nervous system. This is interspersed with appropriate recovery to allow the body to adapt and grow stronger. Which is largely driven by the parasympathetic nervous system.

Which brings us back to HRV.

You can think of HRV as a measurement of allowing adequate stress and adequate recovery be it mental, physical or otherwise. Over stress the system or do not allow adequate recovery and watch your HRV drop. Under stress the system or allow too much recovery and watch your HRV drop. Hit the sweet spot – there you go.

Some final points:

- HRV is one of the most useful metrics you can measure. It is generally accepted that a higher HRV is better but getting to know your own numbers rather than comparing to others is where HRV is of most use. This takes time and requires regular monitoring.

- It should become clear that deterioration in HRV can be driven by any number of factors. In the short term a drop in HRV during a highly stressful period such as a shock load training week or working on a high-pressure deadline may not necessarily be a cause for concern.

- A long period of deteriorating or low HRV, however, may be an important indicator that something needs to be addressed.

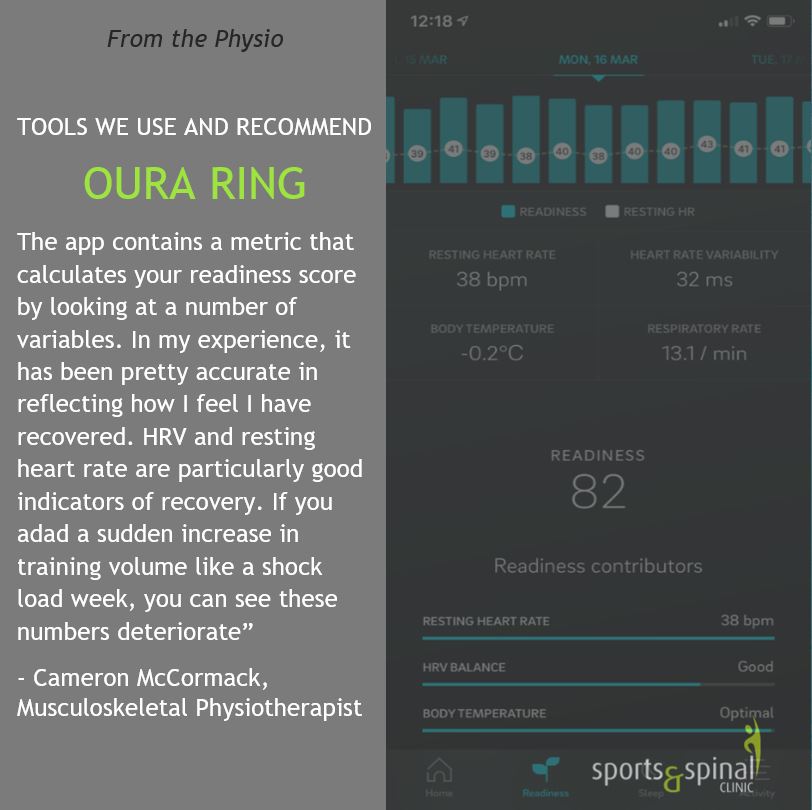

In our upcoming posts we will talk about how we measure HRV and what we have learnt in relation to training load, injury and illness. The Oura Ring App (below) is a good way to track metrics such as your HRV.